Regular readers of the blog will know that we have been

having a contradiction with Brad DeLong and the rest of the

monetarist mainstream of modern macroeconomics.

They think that demand constraints imply, by definition, an excess demand for money or "safe assets." Unemployment implies disequilibrium, for them; if everyone can achieve their desired transactions at the prevailing prices, then society's productive capacity will always be fully utilized. Whereas I think that the interdependence of income and expenditure means that all markets can clear at a range of different levels of output and employment.

What does this mean in practice? I am pretty sure that no one thinks the desire to accumulate safe assets

directly reduces demand for current goods from households and nonfinancial businesses. If a safe asset shortage is restricting demand for real goods and services, it must be via an unwillingness of banks to hold the liabilities of nonfinancial units. Somebody has to be credit constrained.

So then: What spending is more credit constrained now, than before the crisis?

It's natural to say, business investment. But in fact, nonresidential investment is recovering nicely. And as I

pointed out last week, by any obvious measure credit conditions for business are exceptionally favorable. Risky business debt is trading at historically low yields, while the volume of new issues of high-risk corporate debt is more than twice what it was on the eve of the crisis. There's some evidence that credit constraints were important for businesses in the immediate post-Lehmann period, if not more recently; but even for the acute crisis period it's hard to explain the majority of the decline in business investment that way. And today, it certainly looks like the supply of business credit is higher, not lower, than before 2008.

Similarly, if a lack of safe assets has reduced intermediaries' willingness to hold household liabilities, it's hard to see it in the data. We know that interest rates are low. We know that most household deleveraging has taken place via

default, as opposed to reduced borrowing. We know the applications for mortgages and

new credit cards have continued to be accepted at the same rate as before the crisis. And this week's new

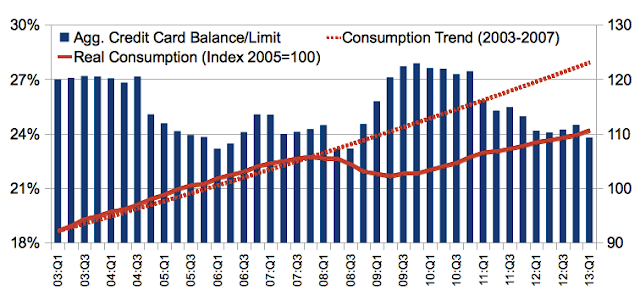

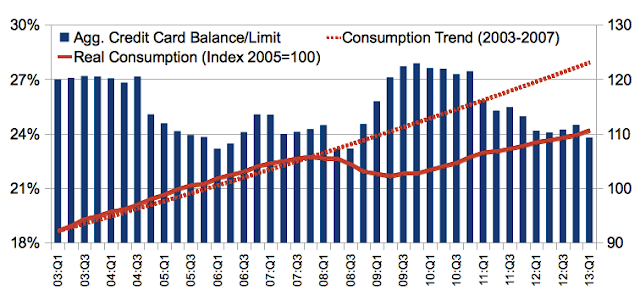

Household Credit and Debt Report confirms that people are coming no closer than before the crisis, to exhausting their credit-card credit. Here's a graph I just made of credit card balances and limits, from the report:

|

| Ratio of total credit card balances to total limits (blue bars) on left scale; indexes of actual and trend consumption (orange lines) on right scale. Source: New York Fed. |

The blue bars show total credit card debt outstanding, divided by total credit card limits. As you can see, borrowers did significantly draw down their credit in the immediate crisis period, with balances rising from about 23% to about 28% of total credit available. This is just as one would expect in a situation where more people were pushing up against liquidity constraints. But for the past year and a half, the ratio of credit card balances to limits has been no higher than before the crisis. Yet, as the orange lines show, consumption hasn't returned to the pre-crisis trend; if anything, it continues to fall further behind. So it looks like a large number of household were pressing against their credit limit during the recession itself (as during the previous one), but not since 2011. One more reason to think that, while the financial crisis may have helped trigger the downturn, household consumption today is not being held back a lack of available credit, or a safe asset shortage.

If it's credit constraints holding back real expenditure, who or what exactly is constrained?